Empathy for your user’s privacy expectations is your compass

Data privacy is a boring topic.

So boring, in fact, that most consumers seem to put it out of their minds as they sign up for service after service and freely give away their personal information to nameless developers who maintain these applications.

So boring that when presented with the choice of a paid application that has strong security and a free service that will monetize them (the user), they usually pick the free option.

So boring that the responsible app developers who take the time to bake in good privacy and security practices find themselves with fewer “features” than the competition.

And there is also a long boring history of data privacy, many centuries worth of abuses by governments, businesses, and individuals collecting and targeting people.

But it’s 2018, and it looks like privacy is no longer “boring”– it’s something you’ll want to consider from day one.

A brief history of data privacy abuses

Unfortunately, the issue of larger institutions using an individual’s data, unbeknownst to the individual, pre-dates the Internet. Census data was used to target Japanese-Americans during WWII, the FBI spied on civil rights activist groups, and the NSA, during heyday of the telegram, set it’s ears on US citizens. That’s just in the US.

In the Internet age, the largest companies are being hacked – be it by individuals, groups, or governments. Here’s a look at the last few years:

- 2011 - Sony PlayStation Network hacked

- 2012 - Yahoo hacked

- 2013 - Snowden leaks; Adobe hacked

- 2014 - iCloud and Snapchat hacked

- 2015 - AdultFriendFinder and Ashley Madison hacked

- 2016 - MySpace, LinkedIn, Experian, and Avast hacked

- 2017 - Ancestry.com hacked

- 2018 - Cambridge Analytica

The Last few years have made it painfully obvious that. . .

- Your personal data is everywhere

- Your government (and probably others) know a lot of it

- Companies find it so valuable that they have been offering you free services so they can have it

- From all of these sources, your data has been sold, resold, leaked, hacked, etc.

- Your personal data is everywhere

For some, this is seen as a hopeless reality. I’ve been hacked, you’ve been backed, we’ve all been hacked. So who cares who has my data at this point? But of course, some of the most important data you have isn’t about the past, but about the future. Where will you be living in a few years? How will your tastes and interests change? Do/Will you have kids? How will you protect their privacy? These thoughts and concerns aren’t lost on the average person and they will be taken into consideration when deciding if your app can be trusted; if your app is worth the risk.

The disconnect between users and companies

Think about what happens when you visit a website or download an app for the first time? Unless the service is friendly to “logged-out” users, the first thing that happens is you are asked for an email and password. Why this information is needed is usually obvious.

- Only you can sign in

- If you forget the password you can get an email sent to you

- Perhaps other important account related emails will be sent

Do you expect your email to be sold to marketing firms? Do you think you’ll start getting spammed by the service? For the average user, if this thought pops into their head, they just don’t sign up and walk away.

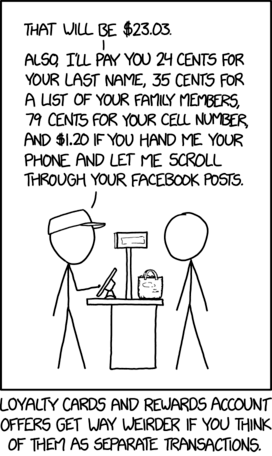

For most users, it might be considered a “risk”, but they sign up anyway as the promising rewards of your app seem to outweigh that risk. And yet, this is exactly the business model of most applications these days.

You might be saying “well. . . most users know what they are getting themselves into.” But consider this example:

With a lot of smartphone apps, you only get one chance to ask the user for a permission. If a user downloads the app and, upon opening for the first time, is asked for camera permission, there is a really good chance the user will say no. If that permission was critical and kills the apps usefulness as a result, the user will uninstall and walk away.

On the other hand, if you let the user into the application, have them click around a little, and then prompt them for camera permission when they try to access a feature that involves taking a picture, the likelihood of them saying yes goes up dramatically. This has become common knowledge now for mobile development, and it’s pretty clear why.

You need a strong connection between the information you’re requesting (camera roll access) and why you’re requesting it (to use your camera and photos to augment the app).

“It’s a matter of trust”

Just as banks over leveraged our money…and crashed in 2008. . .companies like FB have over leveraged our data and are crashing in 2018.

Like a trustworthy bank that takes care of your money, you want to be a good steward of your user’s data.

A good data steward only asks users for the permissions and data they actually need. But be careful, if your app later takes advantage of that permission to do something completely different, you risk crossing a trust boundary.

A good data steward doesn’t imply how the users data is leveraged. Make it very clear what you will use that data for and how long it will remain in your system.

A good data steward gives a user full control of their data. If they no longer want to use your application, they can delete their data and leave. It should be clear to the user what metadata or created data might remain after they leave. Should a user be unhappy with any of this, they should have someone they can call who has the power to address their concerns.

A good data steward controls access to user data – not just from other users on the internet, but also internal employees. To view any user’s personal data, it should require extraordinary circumstantial reasoning.

A good data steward thinks about the user’s need to control and safeguard personal data, and takes actions early in application development to add the necessary features, processes, and policies to ensure those needs are met.

Using these thoughts as your internal compass, you should be in the right mindset to tackle GDPR and other data protection laws as you plan out the features and interactions the applications you build will have.